The digitalization of government at first glance seems like a simple modernization step: from paper to pixels, from counters to websites. But beneath this seemingly simple transition lies a fundamental transformation that has drastically changed the way government functions. In this blog, we explore how the shift from physical to digital processes has not only changed our interaction with government but has also led to unforeseen challenges in the execution of government tasks.

From Paper to Pixels

The execution of government tasks is deeply rooted in a paper tradition. This is more than just a matter of documentation - it has shaped the entire architecture of government processes. Think of physical files in filing cabinets, forms that were sent by mail, and signatures that were put on paper with pen. This paper reality created natural boundaries: documents could only be in one place at a time, had to be physically transferred, and the number of people who had access to information simultaneously was limited by practical constraints.

| Figure 1: Land Registry office (Kadaster) as an example of a physical institution |

With the advent of digital technology, this reality has fundamentally changed. What once existed as stacks of paper in filing cabinets now exists as data streams in server parks. This transformation offers unprecedented possibilities: documents can be shared instantly, thousands of applications can be processed in parallel, and information is accessible anywhere and anytime. But this digitalization has often been laid like a blanket over existing processes, without thoroughly revising the underlying way of working.

The scaling that results from this is monumental. Where a civil servant could once process dozens of files per day, automated systems now handle thousands of cases per hour. However, this exponential scaling has a downside: if there are errors in the system, these also multiply on the same scale. A wrongly programmed rule can affect thousands of citizens in a short time.

| Figure 2: Land Registry office (Kadaster) as an example of a half physical and half digital institution |

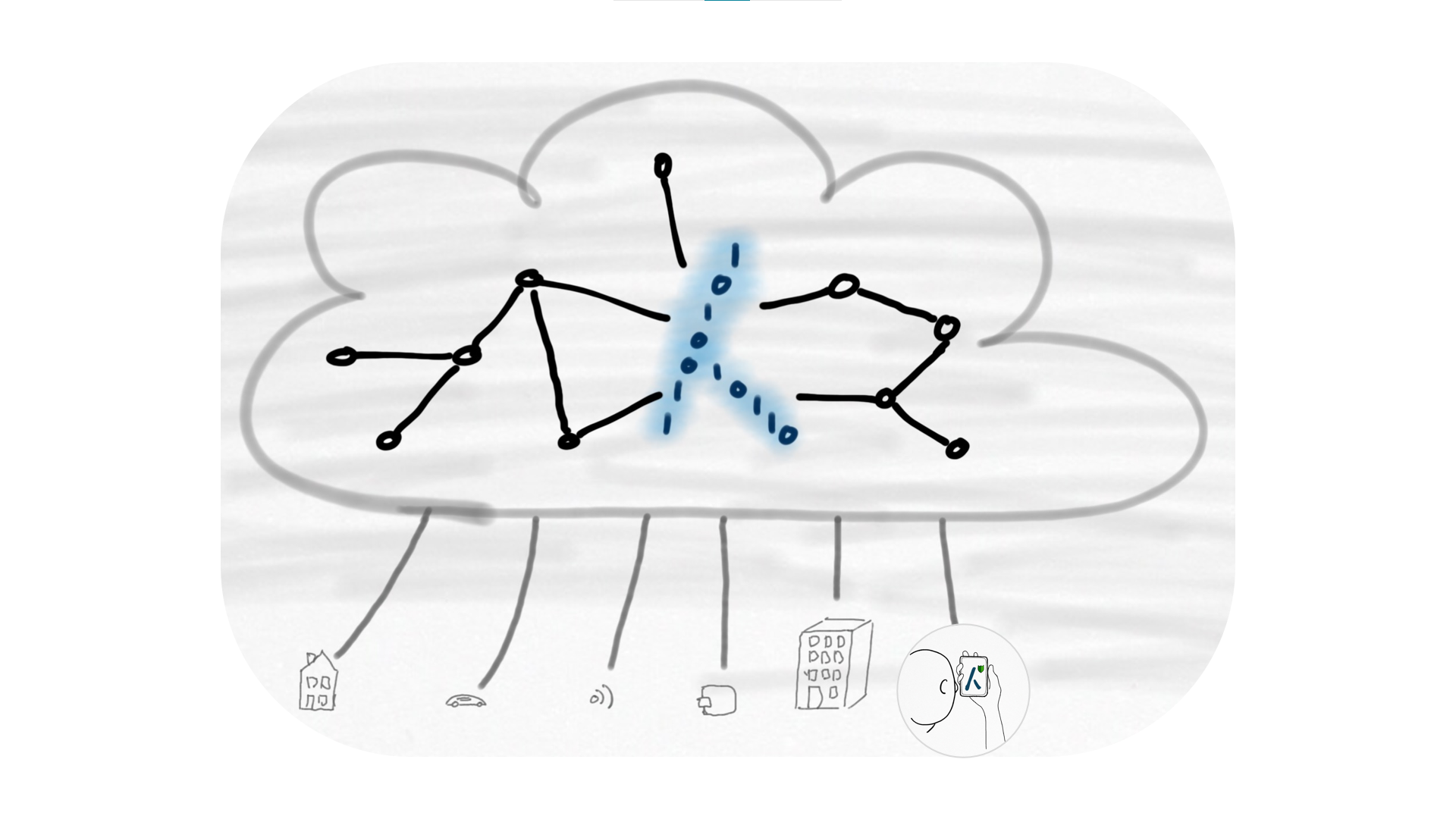

This digital transformation has also fundamentally changed the character of government organizations. The imposing government buildings that once symbolized bureaucratic power and distance are now fading into a network of servers and clouds. Paradoxically, this makes the government both more elusive and more accessible. Through websites and apps, it is available to us 24/7, but the human factor - that civil servant behind the counter who could still think along and provide customized service - is increasingly fading into the background.

| Figure 3: Land Registry office (Kadaster) as an example of a digital institution in the network |

Process Chains

This fundamental shift from paper to digital has perhaps had the greatest impact on chains of processes within and between organizations. In the paper era, the physical route of a file was crystal clear: you could literally follow how a folder went from desk to desk, from department to department, often accompanied by a routing form with signatures and date stamps. These physical limitations created a natural rhythm and automatically created moments of control and reflection.

In the digital world, these chains have seemingly become more efficient. A document can be shared instantly with all parties involved, changes are synchronized in real-time, and process flows can run in parallel rather than sequentially. But this apparent efficiency masks fundamental problems. Where earlier a physical folder could not get ’lost’ - it was always somewhere - digital files can disappear into the depths of different systems that don’t talk to each other. The responsibility for a process becomes blurred when ten departments have simultaneous access to the same information.

It becomes even more complex when different organizations need to collaborate in these chains. Where previously a paper file went from one organization to another, with clear transfer protocols, we now see a web of digital connections emerging. Municipalities, implementing agencies, ministries - they all have their own systems, which are often cobbled together with makeshift solutions. The result is a digital patchwork where information regularly slips through the seams.

| Figure 4: Land Registry office (Kadaster) as an example in the digital patchwork |

The future of these process chains raises fundamental questions. Should we hold on to the old, linear process models that we inherited from the paper era? Or does the digital reality require a complete revision of how we organize processes? Could we, for example, move towards a model in which processes flow more organically, guided by the need of the moment instead of predetermined routes?

And perhaps the most crucial question: how do we safeguard important values such as transparency, accountability, and human customization in this new reality? Because although digitalization offers enormous possibilities for efficiency and accessibility, we must not forget that behind every process, there are ultimately people - both as implementers and as citizens.

The challenge for the coming years will be to find a new balance. A balance between the possibilities of digital technology and the human scale. Between efficiency and thoroughness. Between standardized processes and room for customization. Because ultimately, government action is not about paper or pixels, but about effectively serving society.

Well, we’re not going to solve this in one day. But let’s start the conversation about our process chains, which issues are now prominent in them, and how we can take steps to solve them.

This blog has been used as context for a Digilab event:

During the Day of Future Chains we want to explore with you, using case studies and with special attention to the role of capable registers, what is needed to make progress. More information about the content of this day will follow soon. Put it in your calendar: April 3, 2025!

Author: Marc van Andel is a solution architect and innovator at the Land Registry. He is currently seconded to the RealisatieIBDS program, specifically the emergence of the Federated Data Space. As part of this, Marc is also involved in the From Reliable Source project.